John Wallis (1616–1703) is best known to early modern intellectual historians and fans of Cultures of Knowledge as an archetypal Republic of Letters polymath; Oxford’s Savilian Professor of Geometry, a gifted cryptographer, and keeper of the University Archives who corresponded extensively with the leading continental luminaries of the age. The letters reproduced in Volume IV of The Correspondence of John Wallis (OUP), to which our Research Fellow Philip Beeley is putting the finishing touches, largely reinforce this impression. The missives find the mathematician embroiled in abstruse conversations with Francis Jessop, Christiaan Huygens, Rasmus Bartholin, and Leibniz about methods of tangents, the rectification of the cycloid, and the reinvigoration of scientific meetings at the Royal Society. However, I was intrigued when Philip told me that many of the letters in this volume reveal that in early 1674 Wallis was sucked into an epistolary controversy of an altogether more worldly kind: a bitter dispute over an Oxford tavern.

As an erstwhile historian of early modern intoxicants – a lively and growing field – I found this run of letters fascinating, and I am extremely grateful to Philip and Keeper of the University Archives Simon Bailey for letting me write about them, and also to reproduce some manuscripts and transcriptions, on the blog (and I hope regular readers will forgive this bibulous tangent, or epistolary detour into drink).[1. From a large and growing literature, recent highlights include B. Kümin & B. A. Tlusty (eds), The World of the Tavern: Public Houses in Early Modern Europe (Aldershot, 2002); A. Smyth (ed.), A Pleasing Sinne: Drink and Conviviality in Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge, 2004); B. Kümin, Drinking Matters: Public Houses and Social Exchange in Early Modern Europe (Basingstoke, 2007); P. Withington, ‘Intoxicants and Society in Early Modern England’, Historical Journal (2011); C. Ludington, The Politics of Wine in Britain: A New Cultural History (Basingstoke, 2013); and J. Herring, C. Regan, D. Weinberg, & P. Withington (eds), Intoxication and Society: Problematic Pleasures of Drugs and Alcohol (Basingstoke, 2013).] This is not the first analytical splicing of letters and liquor, and there are many well-known touch points between seventeenth-century drinking houses and learned correspondence, including (to name just a few) the role of inns and their keepers as nodes within postal systems; the consumption, oral dissemination, and scribal circulation of letters within drinking places; and the superimposition of manuscript correspondence networks upon a daily round of face to face exchange of ideas and information – an oral story world, in Sophie van Romburgh’s memorable phrase – traversing the material and social spaces of streets, dwellings, coffee houses, taverns, alehouses, inns, brandy shops, and punch houses as well as libraries and laboratories. As such, some relevant keyword searches in Early Modern Letters Online yield riches for the historian of drinking. However, the vignette below illustrates the cross-fertilization of worlds with an unusual vividness.

A ‘New Erected Tavern’

Detail from Tavern Scene, by David Teniers. 1658 (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC [Wikimedia Commons]).

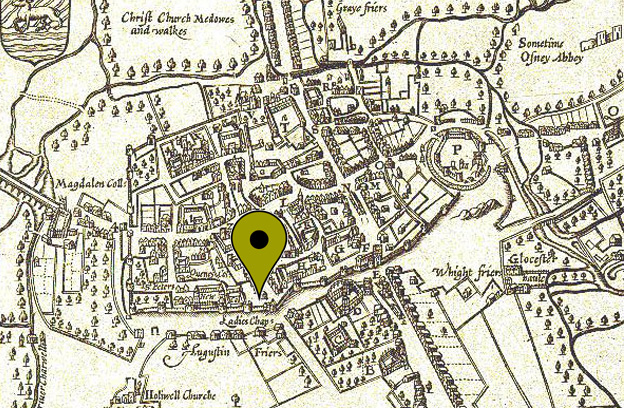

Drinking Geographies: John Speed’s 1605 map of Oxford, with the approximate location of William Stirk’s tavern indicated. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

Plum Spot: Stirk’s tavern would not have been located far away from the present-day King’s Arms.

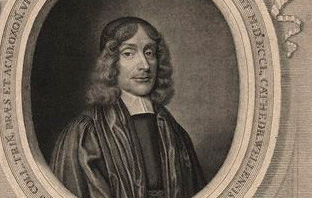

Things did not go to plan. The unilateral creation of a ‘new erected tavern’ at the heart of the collegiate university – literally and metaphorically – infuriated the seat of learning. First off were the disciplinary and moral issues raised by the greater availability of vinous intoxicants amongst such a young, promising, yet corruptible student population (concerns that continue to vex academics and senior administrators to this day). Writing to the Chancellor, the Duke of Ormond, in March, theologian, physician, and Vice Chancellor Ralph Bathurst – who led initial opposition to the rogue drinkery – complained that ‘the new tavern… being not farre from the publick schools [i.e. the academic departments found in the quadrangle of the Bodleian Library], it may so much the more tend to the prejudice of good order and discipline among us’. For Bathurst, the licensing of Stirk was a thin end of a larger wedge, which should be seen in the context of microbe-like proliferation elsewhere in the seventeenth-century city’s out of control alcohol sector: ‘Our alehouses, by reason of the town’s immoderate licensing, and the plausible plea of increasing his Majesty’s excise, are thriven into several hundreds: and what number the taverns may grow to, is not easily to tell’. In a later letter, he wrote ‘I hope that none but Mr Stirke will blame me, if I take care that the youth of this University, whose sober education is of more value to the public than 20l [i.e. £] a year, may not have a free and untroubled liberty to spend their time and money in debauchery’.[3. T. Warton, The Life and Literary Remains of Ralph Bathurst (London, 1761), pp. 104, 110, 119.]

Scourge of Vintners: Vice Chancellor Ralph Bathurst, the theologian and physician who led the initial campaign against Stirk’s tavern.

As serious, however – and one senses strongly that this was the real issue – were the thorny jurisdictional questions of principle, process, and privilege raised in acute form by the unilateral licensing of Stirk on the part of crown and town: as in Cambridge, the University had traditionally enjoyed the sole right of licensing and suppressing taverns, a time-honoured practice bypassed without consultation in this case. As Bathurst put it in his first letter to the Chancellor, ‘[t]he three licenses which the university hath always had in its power to allow, are already possessed and employed: This now derives its authority from the wine-office, and boasts, that it shall be maintained against all opposition whatsoever. Our privileges are herein deeply concerned’. In a later letter, he urged the Chancellor ‘to vindicate us and and our priveleges from these great incroachments; or at least, permitt us to make use of our owne lawes and power to restrain them’.[4. Ibid., pp. 104, 110.]

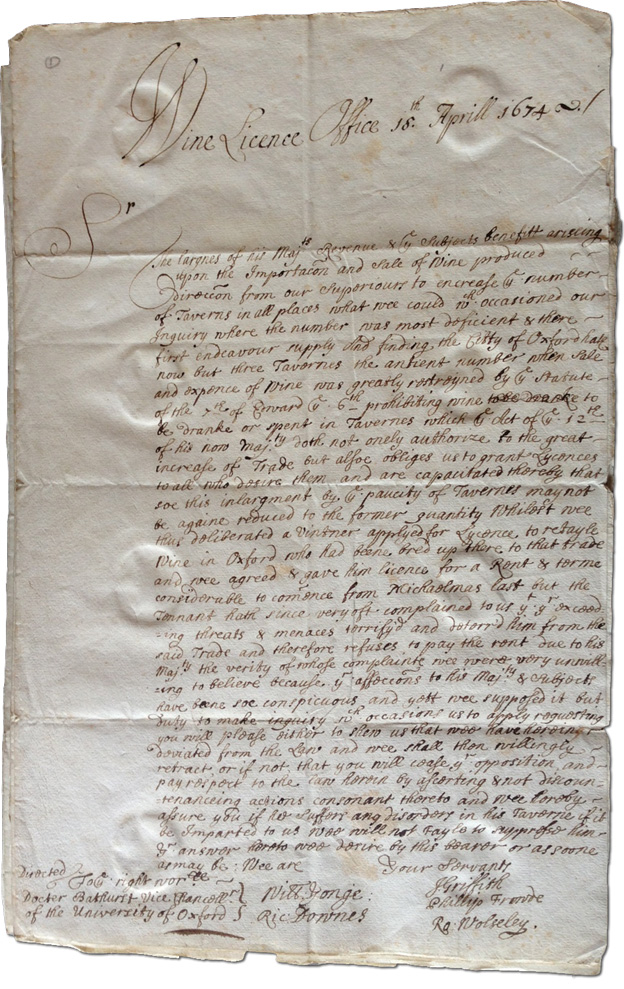

Their umbrage aroused, it seems that from the outset of his tenure the University made trading conditions extremely difficult for the hapless Stirk, harassing him at his premises and imposing penalties on students who were found visiting this trendy new nightspot. Indeed, so detrimental were the commercial obstacles thrown up by Bathurst’s heavies that Stirk refused to pay his £20 annual rent to the crown, which brought matters to the swift attention of the Wine Licence Office and the rapid escalation of the controversy. The opening salvo came on 18 April, when five of the seven wine commissioners wrote to Vice Chancellor Bathurst from Durham Yard setting out their case. They emphasized the need for additional ‘supply’ in Oxford’s case (the city, it was claimed, had a ‘paucity of taverns’), that Stirk was the right man for the job (he was ‘bred up there to that trade’), complained about the University’s ‘exceeding threats and menaces’ towards their ‘terrified’ keeper, and requested that ‘you will please either to shew Us that we have herein deviated from the Law, & when We shall willingly retract, or if not, that you will cease your Opposition & pay respect to the Law herein’.[5. Oxford University Archives, WPβ/15/8, No. 1.] When this letter failed to elicit the desired response, in characteristic early modern fashion the Wine Licence Office got litigious and brought a suit against the University in the Exchequer of Pleas at the end of that month.[5. Oxford University Archives, WPβ/15/8, No. 8.]

Opening Gambit: The first letter from the Wine Licence Office to Vice Chancellor Bathurst, defending their actions and complaining about the University’s treatment of Stirk. Oxford University Archives, WPBeta/15/8, No. 1.

Wallis Amongst the Taverns

Who You Gonna Call? Tavern-buster John Wallis.

With the dispute spiralling and now facing legal action, the University invoked their secret weapon; as Bathurst described him, ‘Dr Wallis, one of our public professors, and custus archivorum’.[6. Warton, Bathurst, p. 117.] Thus began Wallis’s involvement in the affair. The choice of one of the architects of infinitesimal calculus – who Bathurst later described as ‘our agent’ – to spearhead the University’s case against the upstart tavern is less surprising than it might at first appear. The mathematician was revered as one of the finest analytical minds of his generation, and also had noted skills as a rhetorician, not least due to his celebrated contributions as a correspondent. Woven deeply into Oxford’s institutional fabric by means of his Savilian chair of geometry, he had also earned a reputation for dogged loyalty (as Bathurst put it, he is a ‘true friend of universities’),[7. Ibid., p. 107.] while his role as keeper of the university archives put him within fingertip reach of the stacks of precedent-rich documents that would be needed to make the case. For his part, notwithstanding his manifold commitments to higher learning and the global Republic of Letters, Wallis – no great frequenter of drinking places himself – clearly welcomed another opportunity to further ingratiate himself with the University brass, and threw himself enthusiastically into his newly appointed role as tavern-buster.

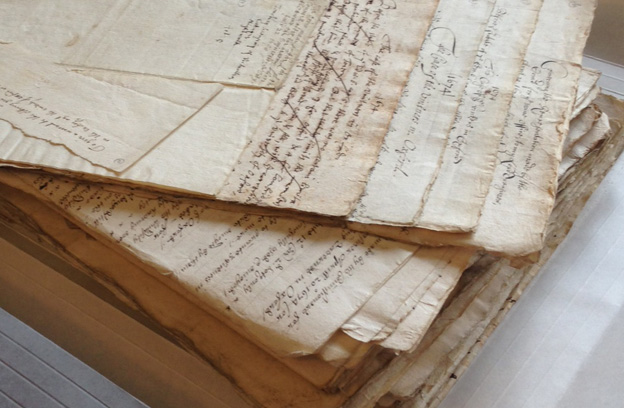

His first and main task was to draw up a ‘breviary’ entitled ‘The Case of the Vintners in Oxford, 1674’ (pdf); ready by May 8, this detailed compendium of relevant legislation and legal precedents involved Wallis in an extensive paper-chase through the statute books and the administrative archives of both Oxford and Cambridge, and exists in several manuscript versions in various hands, one of which was send to the Chancellor, and another to the Lord Treasurer at the Exchequer of Pleas who would be deciding the case.[8. Wallis’s original at Oxford University Archives, WPβ/15/8, No. 4.] In this key document, Wallis sets out a strong common law defence for the University, focusing for the most part on Oxonian and Cantabrigian test cases where the sole right of University officers to licence and suppress taverns was upheld by the courts. This includes the interesting case of John Keymer’s tavern in Cambridge in the late sixteenth century; licensed by collector of wine rents Sir Walter Raleigh in defiance of that University’s wishes, this was shut down at the behest of the Privy Council when the proctors complained that their jurisdiction was ‘molested’ (the campaign of terror waged against Keymer and his wife, described in his ODNB entry, is probably similar to that experienced by the star-crossed Stirk). It also summarises the local cases of ‘Mr Alderman Potter’ (a wool-draper and rogue taverner squashed by the Vice Chancellor in 1620), and of ‘Mrs Turton’ (a town-licensed tavern-keeper suppressed at the behest of the University in 1661). After several pages of careful documentary proofs Wallis’s conclusion was brief but devastating: ‘[T]he present New Tavern… erected by license from the Wine Office, is manifestly destructive to our Rights’.

Documenting Drink: Four scribal copies of ‘The Case of the Vintners in Oxford, 1674’ (with Wallis’s original draft uppermost), pictured on top of the stacks of documents Wallis used in preparing his case.

Further to his creation of ‘The Case of the Vintners’ – which was followed up by a briefer, point-by-point rebuttal to the Wine Licence Office’s own representation to the Exchequer of Pleas later in May[9. Oxford University Archives, WPβ/15/8, No. 8.] – Wallis remained on top of developments throughout the remainder of 1674 and the first part of 1675, corresponding regularly with Bathurst, legal representatives, and seasoned veterans of tavern wars in Cambridge, and making frequent sorties to London with the University’s solicitor William Hopkins. Indeed, the case seems to have rumbled on as a result of stalling on the part of both the Exchequer of Pleas and the plaintiffs at the Wine Licence Office; perhaps recognizing the strength of the University’s defence as prepared and argued by Wallis, hearings with the presiding Lord Treasurer were convened at impracticably short notice, abruptly cancelled, or not scheduled at all. In the intervening period (in Bathurst’s words), ‘the new tavern set up here in opposition to our privileges, still continues to our great inconvenience, and has occasioned us no small trouble and charges’ (for their part, the Wine Licence Office also wrote to Bathurst in January 1675 complaining about his ‘further severity against Mr Stirk’).[10. Warton, Bathurst, p. 127; Oxford University Archives, WPβ/15/8, No. 9.]

Foot Dragging: Detail from the Wine Licence Office’s January 1675 letter to Bathurst, complaining about the University’s ‘further severity against Mr Stirk’ and urging them to cease harassment until the oft-delayed hearing before the Lord Treasurer at the Exchequer of Pleas. Oxford University Archives, WPBeta/15/8, No. 8.

Friends in High Places: Peter Mews, former Oxford Vice Chancellor and Bishop of Bath and Wells, whose intervention brought a swift resolution to the case.

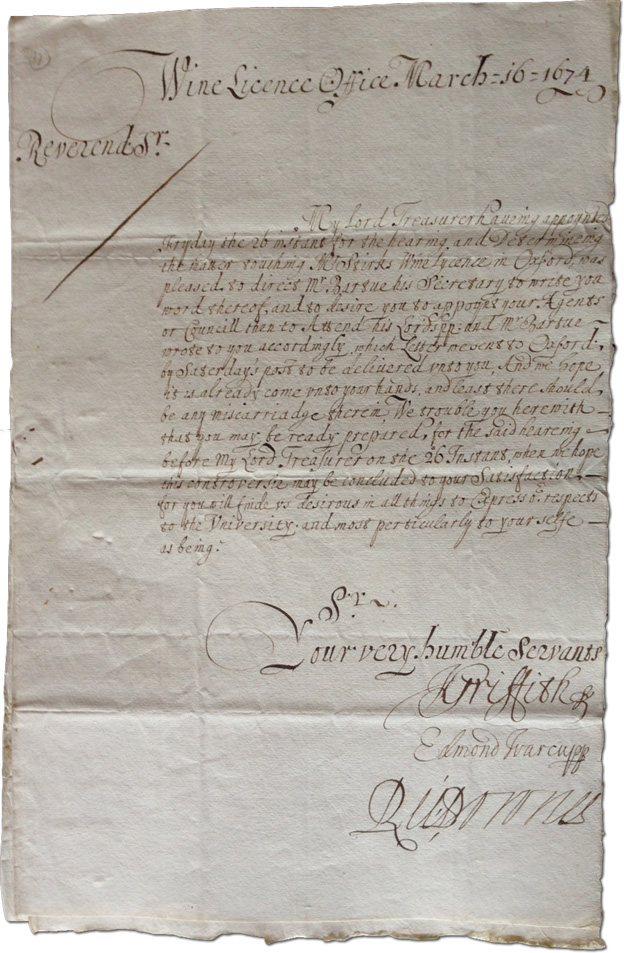

After nearly a year of ‘tedious, chargeable, and fruitless attention’, and several unanswered epistolary Exocets to London clerks on the part of Wallis, the enterprising mathematician wheeled out the big guns in a letter dated 16 March 1674/5, and sent to Peter Mews at his Charing Cross lodgings; Mews was not only Bathurst’s immediate predecessor as Vice Chancellor, but – more usefully for the embattled Oxonian tavern-busters – was by now the high-ranking Bishop of Bath and Wells. In this lengthy document, Wallis complains in vigorous terms about ‘the tavern… sett up to confront us’, and also about the stalling of the case on the part of the Wine Licence Office, the Exchequer of Pleas, and the Lord Treasurer.[11. Oxford University Archives, SP/D/6/18.] Mews replied to Wallis modestly (‘You may assure your selfe of my utmost endeavers to serve the University so far as my small interest in those Persons who are concern’d may be usefull’),[12. Oxford University Archives, SP/D/6/19.] but his intervention had a swift and decisive effect, for that very same day – 16 March 1674/5 – the London wine commissioners mailed to Bathurst an extremely conciliatory, almost obsequious response. Within it, they referred to a letter they had sent to him confirming a date for a hearing (set for 26 April), ‘which letter we sent to Oxford by Saturday’s post to be delivered unto you’.[13. Oxford University Archives, WPβ/15/8, No. 11.] We know from Wallis’s letter to Mews that this missive was indeed received by Bathurst on the Saturday in question (‘Mr Vice-chancellor having last Saturday, received summons…’), providing further evidence of the speed and efficiency of the Oxford-London postal axis in this period, especially when galvanized by disputed drinking places.

The Speed of the Post: The Wine Licence Office’s final letter to Vice Chancellor Bathurst, setting a date for the hearing, and containing some information about the efficiency of the Oxford-London epistolary axis. Oxford University Archives, WPBeta/15/8, No. 11.

Conclusions

The writing was on the wall as well as on the parchment; the hearing, which seems to have finally taken place over two days between 28 April and 5 May 1675, found in favour of the University, and Stirk – another high-profile vintner scalp for an early modern Vice Chancellor – was officially discharged of his licence and finally closed for business in June.[14. Oxford University Archives, WPβ/15/8, No. 28.] However, regardless of this somewhat predicable result, some more general conclusions emerge from this bibulous case study. From the perspective of the historian of alcohol, it offers a fascinating insight into the workings of the wine trade in the unique, if not entirely representative, setting of a University city;[15. For a demand-side case study based largely on material from Cambridge see A. Shepard, ‘Swil-bolls and tos-pots’: Drink Culture and Male Bonding in England, 1560–1640’, in L. Gowing, M. Hunter & M. Rubin (eds), Love, Friendship and Faith in Europe, 1300–1800 (Basingstoke, 2005).] indeed, even if the situation sketched here is far from typical, it offers a reminder of the importance of local frameworks in structuring drinking landscapes, of the close yet highly contested relationship between central and local authorities and apparatuses in the regulation of alcohol, and in particular of the almost unique capacity of early modern intoxicants to engender and crystallize turf wars over jurisdictional privilege that reached far beyond tavern walls (something I have argued in a different context elsewhere).[16. J. Brown, ‘Alehouses and State Formation in Early Modern England’, in Herring, Regan, Weinberg, & Withington, Intoxication, pp. 110-132.] And from the perspective of correspondence networks and the great worldwide sweep of the Republic of Letters – specifically, through the instrumentality of John Wallis to the successful pursuit and resolution of the case – it reminds us that the life of the mind in early modern Europe was not abstract or free-floating, that scholarly correspondents were embedded in complex life-worlds (especially when, as was so often the case, they were required to wear so many different hats), and that there was perhaps no such thing as a ‘learned correspondence’, hermetically sealed from seepage from the quotidian and the everyday.

[vc_text_separator title=”Notes” title_align=”separator_align_center” width=”1/1″ el_position=”first last”]

Pingback: The Giants’ Shoulders #62: Alpha Pappa | A Glonk's HPS Blog