Have you spotted the women looking out from the niches on the home page in EMLO? Today’s array of new catalogues marks the launch of Women’s Early Modern Letters Online [WEMLO], a resource and discussion forum for all early modern women’s correspondence held within EMLO.

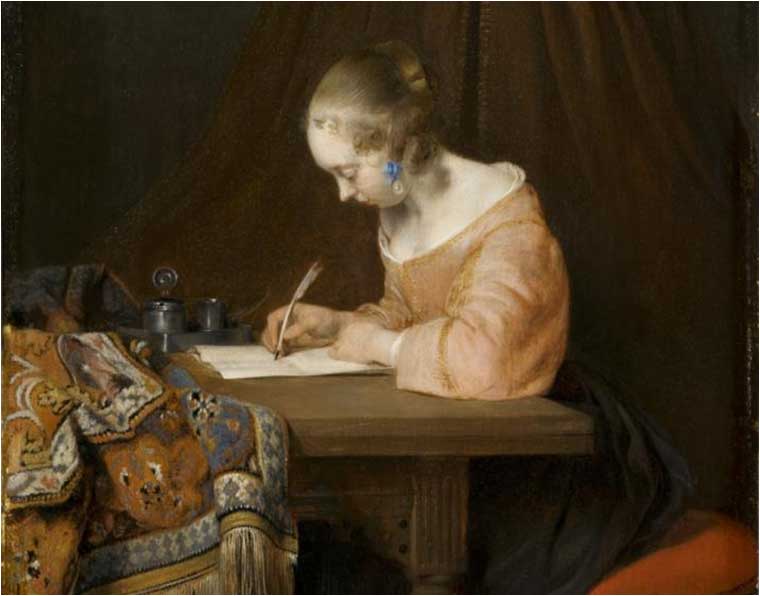

Woman writing a letter, by Gerard Terborch. c.1655. (Mauritshuis, The Hague; source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

In 2012, Professor James Daybell and Dr Kim McLean-Fiander (the latter a former colleague from Cultures of Knowledge during its first phase), received British Academy/Leverhulme funding to bring together a community of scholars working on early modern women. Their research interests focussed on a number of key correspondences of late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth century women, the metadata for which had been collated previously over several years by James Daybell. The WEMLO project organized a series of workshops, at which scholars identified the need for a epistolary union catalogue tailored to allow searches by female correspondents, filters for letters written or received only by women, and the ability to interrogate both women’s name records and their correspondences against those of their male counterparts. Our lead developer, Mat Wilcoxson, took thse desiderata into his ‘alchemical laboratory’, and his success in this work is the cause for the first part of our celebrations today.

We are delighted also to announce the WEMLO Network and Resources hub, a bespoke area (similar to the virtual exhibition space launched in November last year to mark the Quatercentary of the dissenter Richard Baxter) that in the future will be a forum for scholars to explore, discuss, and showcase early modern women’s epistolary culture. Our third cause for celebration today is the publication of five new catalogues — those of Lady Anne Bacon; Margaret Clifford, countess of Cumberland; Anne Dudley, countess of Warwick; Lady Penelope Rich; and Lady Arbella Stuart — all of which are taken from or are based on James Daybell’s metadata. Within the next few months, a number of additional catalogues from James’s accumulated wealth of curated metadata will be published, including those for Elizabeth Bourne, a Tudor poet and prolific letter writer; Sabine Johnson, a Tudor merchant’s wife; Lady Elizabeth Russell (née Cooke and the sister of Lady Anne Bacon) — as well as several more catalogues compiled by members of the WEMLO community. Scholars may be interested to know that catalogues for Elizabeth of Bohemia, Bess of Hardwick, and a collection of the correspondences of six wives of the Dutch and Frisian stadholders are all in preparation at present and will be released in EMLO this autumn.

Over the past few weeks, as the Digital Fellows and I have worked to prepare for upload the metadata of the five WEMLO catalogues, numerous letters caught our collective eye, some on account of a beautiful hand or a distinctive voice, others because of the content. Indeed, we found ourselves in the office reading many aloud. Were we to vote, I suspect our favourite might be that of Lady Anne Bacon writing to one of her sons — Anthony (brother of Francis) — as she did so often to offer advice regarding his gout and urging him to use his ‘leggs betymes for fear of loosing in disuse’. This just a week after she had sent him ‘a hogshead of November bere . . . and a barrell also of the same bruing’. Irrespective of gout, you are all most welcome to join us tonight as we raise a glass in celebration of this vibrant scholarly community that is WEMLO (from 6pm in Oxford’s Faculty of History on George Street). We hope you enjoy these new correspondences and will take advantage of the links that have been provided, where these were available, to manuscript images, transcripts, and printed copies of the letters. The early modern women you find on EMLO’s home page today are just the beginning: in the coming months and years you will encounter many more daughters, wives, mothers, widows, spinsters, nuns, and dowagers in our online resources. Many are strong, formidable, and talented women — from political rulers in their own right, to literary and scholarly figures. John Knox might not be happy, but most certainly we are!