The early modern individual whose calendar of correspondence is the latest to be published in EMLO may have been described as ‘invaluable’ by Alfred Rupert and Marie Boas Hall in their edition of Oldenburg’s correspondence, but one or two additional adjectives come to mind when considering his life: elusive, intriguing, curious, adventurous, and tragic — any one of these could be applied to Francis Vernon.

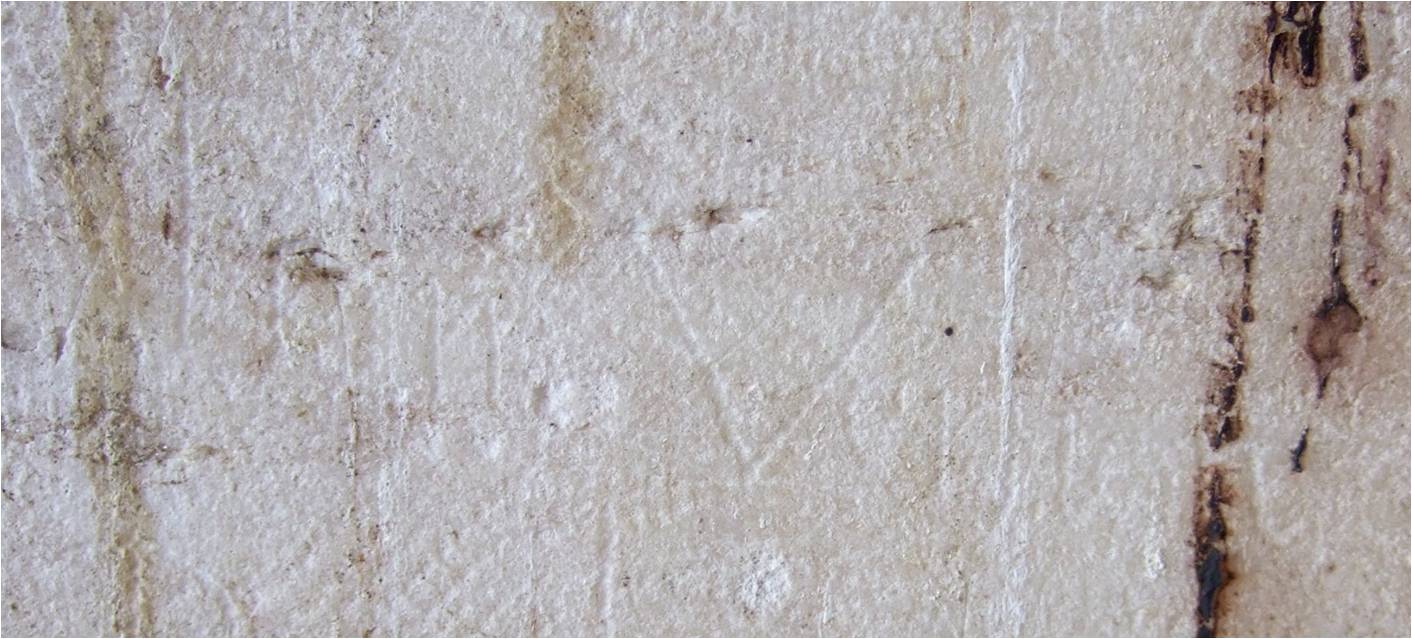

A memorial of Francis Vernon’s visit to Athens in 1675: his name carved on a marble wall inside the Temple of Hephaestus, on the Agora. (source of image: Alexandre J. Tessier)

Vernon, who was born in 1637, was the only Fellow of the early Royal Society to have had the misfortune to have been captured by Barbary pirates and held thereafter for a number of months as a slave. Between 1669 and 1672 he was based in Paris, where he worked as a diplomatic agent, but Vernon was also an adventurer who travelled across Europe as well as the length and breadth of the Mediterranean. He was well educated, eager for knowledge, and he spoke multiple languages. Vernon visited and made notes on ancient Greek sites that are still of relevance to archaeologists three-and-a-half centuries later, although perhaps we should not be admitting that he indulged in early modern graffiti and could have been charged today with criminal damage: his name is to be found carved into a marble wall of the temple of Hephaestus. In the course of his final journey, Vernon survived a second attack by pirates but was killed in a fight, most likely early in 1677 and somewhere near Isfahan, seemingly in a dispute over the theft of his knife. Few details of the events surrounding his untimely death are certain. What we do know, however, is that his was no ordinary life and his was no ordinary talent.

The French scholar, Alexandre J. Tessier, who has worked in detail on Sir Joseph Williamson (1633–1701) and his correspondents, collated the calendar of correspondence sent from Vernon, who was based in Paris, to Williamson, who was located at the English court. Dr Tessier has extensive knowledge of the postal system of this period and has conducted significant research in the field, a consequence of which is that users will find, for these letters, the recorded dates of receipt. Dr Tessier’s calendar may be viewed alongside that of the letters exchanged between Vernon and Oldenburg which were published by the Halls in their indispensible edition of Oldenburg’s correspondence. We hope this arrangement of parallel calendars within EMLO will prove useful, and we have set up in addition a search whereby users may view letters from all the correspondences in the union catalogue that are from, to, or mention Vernon.

One mystery concerning Vernon that might be possible to resolve involves his portrait, which was recorded last in a sale at Sotheby’s, London, on 25 April 1934. The painting, which had been in the possession of C. E. Dashwood, of Wherstead Park, near Ipswich, was described as ‘Venetian School’ and dated to circa 1660. It was a half-length portrait, inscribed on the back as follows: ‘Portrait of Mr. Vernon . . . a man of distinguished learning and ingenuity, who disliking ye measures of King Charles Government refused considerable employment and travelled into the East, where he made many valuable collections, most of which were lost by his untimely death[.] he was taken prisoner by the Algerines and returning to Venice, where he was ransomed, was painted in ye slaves dress at ye request of an eminent painter…’ A second version of the portrait, a copy, was sold as the subsequent lot. Dr Tessier has attempted to track down these portraits, thus far without success. Should anyone happen upon an image of Francis Vernon dressed his slave outfit, please be in touch …