In the main it is for his association with key members of the circle known as the Cambridge Platonists that John Worthington (1618–1671) is remembered today. However, a sub-set of letters contained within EMLO’s catalogue of Worthington’s correspondence charts the friendship between the German-born Samuel Hartlib and this English clergyman, translator, and editor. These letters tell also of the latter’s involvement in Hartlib’s legacy. The erstwhile Cultures of Knowledge post-doctoral researcher Dr Leigh Penman has pieced together in meticulous detail the fate of the intelligencer’s papers between 1662 and their ‘re-discovery’ in a solicitor’s office in 1933; it turns out that a journey north from London to Cheshire which Worthington undertook in the autumn of 1666 and his subsequent residency at Brereton Hall the following winter helps to plug what had been previously a crucial gap in the afterlife of this archive.[1. Leigh T. I. Penman, ‘Omnium Exposita Rapinæ: The Afterlives of the Papers of Samuel Hartlib’, Book History, 19 (2016), pp. 1–65.]

In conjunction with the entries in his diary, Worthington’s letters tell of the series of misfortunes that befell him in the unsettled years following the end of the Commonwealth and the restoration of the Stuarts. Six years into the reign of Charles II and just four and a half years after Samuel Hartlib’s death at his home in Axe Yard, Westminster, Worthington found himself in the autumn of 1666 with access to the papers that made up the remnants of his old friend’s archive. ‘I met with two trunks full of Mr. Hartlib’s papers, which my Lord Brereton purchased’, he recalled later on 10 June 1667 to Nathaniel Ingelo. ‘I thought they had been put in order, but finding it otherwise, I took them out, bestrewed a great chamber with them, put them into order in several bundles, and some papers I met with not unworthy of your sight.’[2. Letter of 10 June 1667, Worthington to Ingelo; James Crossley and Richard Christie, eds, The Diary and Correspondence of Dr. John Worthington, 2 vols in 3 (Manchester, 1847–86), vol. II, part I, pp. 229–33.]

Brereton Hall, Cheshire, before 1829. Engraving. (Source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

Worthington had accepted an invitation from William Brereton, third Baron Brereton of Leighlin (1631–1681), and moved to Cheshire as preacher at Holmes Green and household chaplain. Fellow guests at Brereton Hall included the mathematician (and former tutor of Brereton) John Pell (1611–1685); Hartlib’s son-in-law Frederick Clodius (1629–1702) and his wife Mary (Hartlib’s daughter, d. c. 1668); Daniel Hartlib (the intelligencer’s Danzig-born nephew, fl. 1657–1677), and Francis Cholmondeley (1636–1713). Robert Boyle (1627–1691) had been invited also, but had declined.[3.For the life of Frederick Clodius, see Vera Keller and Leigh T. I. Penman, ‘From the Archives of Scientific Diplomacy: Science and the Shared Interests of Samuel Hartlib’s London and Frederick Clodius’s Gottorf’, ISIS, 106, no. 1 (2015), pp. 17–42; and for an account of this gathering at Brereton Hall, and the aspirations of William in drawing this circle together, see Penman (2016).] Dr Penman has deduced that Brereton bought Hartlib’s archive from the intelligencer’s son, young Samuel (1631–after 1690), sometime in 1664.[4. Penman (2016), p. 14.] The convergence of Hartlibian figures at Brereton Hall appears to have been part of an attempt to further a scheme wholly in keeping with the ideals of the deceased reformer, namely one that would result in the education and relief of the poor of Cheshire, assisting with the provision of education and optimal husbandry, whilst working more generally for universal reform. Despite having family in Manchester (where he had been born), Worthington explained in a letter some years later to Elizabeth Foxcroft: ‘Nothing did or could more induce me to that northern journey I took in the year 1666 but that I was told by one that he did exceedingly affect and would begin such a design of Christian societies if I would remove thither. And if I would take pains there and preach sometimes abroad, he would allow me a competency a year . . .'[5. Letter from Worthington to Elizabeth Foxcroft, c. 1670–1671; Crossley and Christie, vol. II, part I, p. 228.] Brereton was not able to fulfill promises to the assembled company, however, and the circle crumpled, together with its aspirations, as members disbanded and drifted elsewhere.

Prior to his departure in April 1667, the letters Worthington wrote from Cheshire offer a sequence of fascinating glimpses into his time spent with Hartlib’s papers. Clearly he must have suggested to Seth Ward (1617–1689), for example, that the latter’s letters be removed, for the then bishop of Exeter wrote on 15 March 1666/7: ‘I am very glad that the papers of Mr. Hartlib are preserved, and that they are fallen into your hands, who are able and disposed to make the best of them . . . those letters of mine own which concerned either Hevelius or Mercator, which although I have forgotten, yet so much I am sure of that they were carelessly and perfunctorily written (or else, indeed, they had not been mine), so that it will be to my advantage to suppress them. However, sir, I leave them wholly to your disposal, either to bring them to me, when I may have the happiness to see you, or to burn them, or leave them among the rest.’ [6. Letter of 15 March 1667 from Ward to Worthington; Crossley and Christie, vol. II, part I, p. 226–7.] Ward’s letters are not to be found today in the Hartlib Papers in the Hartlib Papers at Sheffield University Library.

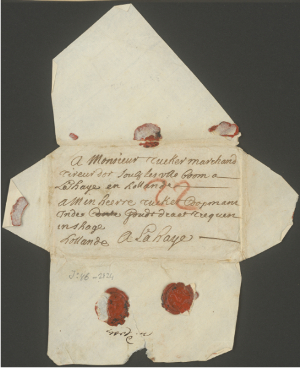

The reason Worthington had accepted Brereton’s invitation in the first place, however, was not to sift through Hartlib’s papers. Rather, from September of 1666, he was no longer in a position to refuse. St Benet Fink in Threadneedle Street, where he had been rector since May 1665 and where he had worked throughout the course of the plague took hold that year across the city, had been destroyed in the fire of London. Worthington’s own house had been razed, many of his possessions were lost, his church and his parish lay in ruins.

Map showing the extent in London of the Great Fire of 1666, by Wenceslas Hollar. Engraving [with a red circle added to indicate the location of St Benet Fink]. (Source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

Fire, and the ever-present fear of it, dogged both Worthington and his old friend’s archive. Indeed, the entire society assembled in Cheshire almost fell victim to it, along with Brereton’s rump of Hartlib’s papers. On Saturday, 12 January 1666/7, Worthington wrote in his diary, ‘at about twelve o’clock, was a fire in Mr. F. C.’s bed. His cap (a napkin about his head) was in part burnt; and his pillow, bolster, and sheet in part. He was fast asleep. Our maid being up then (which was unusual) and sister Hephzibah Whichcote smelt the fire, found our hall full of smoke, looked into one part of the house, but could find no fire. At last they knocked on Mr. F. C.’s door and awakened him, who was near to be burnt in his bed, and so might we all have been burnt. God be praised for his preservation.'[8. See Crossley and Christie, vol. II, part 1, pp. 223–4. ‘Mr. F. C.’ is identified in a note as Francis Cholmondeley. It’s possible, however, that ‘Mr F. C.’ could refer to Frederick Clodius. Hephzibah Whichcote was the sister of John Worthington’s wife Mary, and both women were nieces of Benjamin Whichcote.]

Nor was this the first escape from fire for Hartlib’s archive. On 6 February 1661/2, Hartlib wrote to Worthington that it ‘pleased God to visit my chamber with a very sad and fearful accident of fire.’ An iron stove in his chamber, stoked by his own son, Sam, had overheated; ‘many of my things were spoiled’, Hartlib wrote.[9. Letter of 6 February 1662, Hartlib to Worthington; Crossley and Christie, vol. II, part 1, pp. 106–7.] Although the papers are not mentioned here as having fallen victim in any way, Worthington had remarked previously on the ‘many bundles of paper’ in Hartlib’s study.[10. Letter of 26 October 1661, Worthington to Hartlib; Crossley and Christie, vol. II, pt. 1, p. 67.] Worthington’s words of consolation, ‘I was sorry to hear of your late danger by the fire in your study, which might have been more devouring and terrible had it been in the night. I hope that the violence was prevented from destroying many of your papers‘, did little to console his friend, who died the following month on 10 March 1662.[11. Letter of 24 February 1662, Worthington to Hartlib; Crossley and Christie, vol. 2, pt. 1, p. 110.] Although the threads that weave in and out of these surviving texts tell sad tales of dreams shattered and aspirations unachieved, the connections between the individuals involved are complex. How and why this group converged upon Brereton Hall is itself a story that cries out to be explored, and where better place to start than with John Worthington.

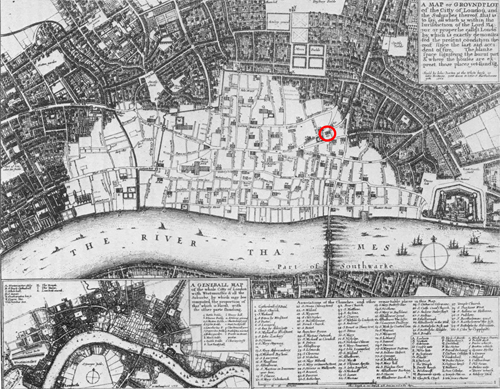

Celebrations are afoot in The Hague following the reopening last weekend of the city’s

Celebrations are afoot in The Hague following the reopening last weekend of the city’s