In recent weeks Cultures of Knowledge has played host to a number of COST-funded ‘short-term-scientific-mission’ visitors, one of whom has been considering how best the project’s current prosopographic data-model might be expanded to include a number of less-easily quantifiable categories, many — but not all — of which pertain to the lives of women.

One area under scrutiny is that of education. In a male-centric model, fields tend to be event led: for example, who attended a certain school between which years under a known headmaster; who matriculated to which university on a particular date; and who was awarded which degree when. But less quantifiable information should be captured in addition: which languages could an individual read, and which speak; whether the parent of a child was involved directly in his or her education; whether the individual in question was the owner of a library and, if so, which books did it contain, and to whom were these bequeathed. The answers to these questions can be highly revealing and they are of especial relevance to the subject of EMLO’s most recently published catalogue, Jan Gruter.

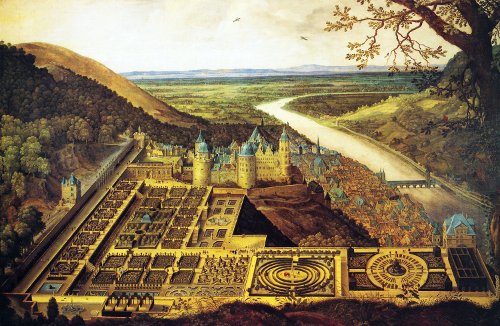

View of Heidelberg before July 1622, by Jacques Foucquier (d.1659). (Kurpfälzisches Museum, Heidelberg; source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

The poet, philologist, and librarian Gruter [Janus Gruterus] was a first-class linguist, studying at Cambridge and at Leiden, and teaching at Rostock, Wittenberg, and Heidelberg, before taking up the position of librarian of the Bibliotheca Palatina in 1602 following the death of Paul Melissus. In addition to becoming caretaker of one of early modern Europe’s most remarkable treasures, Gruter assembled a significant personal library of his own. Both libraries suffered immeasurably following the capture of Heidelberg by Tilly’s imperial troops in September 1622 and a significant portion (the Latin and Greek manuscripts) of the Bibliotheca Palatina was taken to Rome as ‘spoils of war’ and was presented there to Pope Gregory XV. The German manuscripts were left behind, however, and may be consulted in Heidelberg today. Gruter, the man of many languages, fled south to Tübingen and Bretten.

Much of the finer detail regarding Gruter’s life is known from the panegyric published in 1631 by one of his pupils, Balthasar Venator. Perhaps the most remarkable fact passed down by Venator is the information about Gruter’s mother, Catherine [Catharina] Tishem [Thysmans]. Catherine was an English woman, from Norwich. She was highly educated, fluent in Latin and Greek (and with a tendency to read Galen in the original), in addition to French, Italian, and English. She taught her son his languages. This will not be news to scholars within the WEMLO network, nor is it unusual for a mother to take charge of the early education of a young family. It is, however, a category of information that needs to be considered and recorded wherever possible for early modern individuals: which languages could a person read, and which write. Might it emerge that a significant number of women were better educated than has been assumed previously? Who stands in the shade behind every great man? Well, behind Jan Gruter, it was Catherine Tishem, a woman whose exceptional skills were recognized, I am pleased to note, by George Ballard in his 1752 publication Memoirs of several ladies of Great Britain, who have been celebrated for their writings, or skill in the learned languages, arts and sciences.