It is a sad truth that only very small number of early modern women received an education. Fewer still benefitted from the education that was on offer to men. Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678) was an inspirational exception, however. Considered today to be the first female university student in Europe, this scholar, poet, linguist, painter, and engraver became one of the most learned women of her age, and EMLO is truly thrilled to be publishing this week a catalogue of her correspondence in partnership with the innovative Utrecht-based project Sharing Knowledge in Learned and Literary Networks (SKILLNET): the Republic of Letters as a pan-European Knowledge Society.

Born in Cologne, Van Schurman lived as a child in Utrecht (the city to which her parents had moved in a bid to escape religious persecution) and in Franeker; she was educated as an equal alongside her brothers. Following the death of her father in 1623, and after re-settling three years later for a second time in Utrecht where she moved into a house near the Domkerk, her reputation as a scholar began to spread, particularly with respect to theology and philosophy, and her knowledge of — and skill in — at least fourteen languages became widely renowned. To celebrate the foundation of the university of Utrecht in 1636, Van Schurman was invited to write a poem in Latin and she used this opportunity to lament the exclusion of women from formal education. This prompted — as the scholar Dr Pieta van Beek has shown in her fascinating publication The first female university student: Anna Maria van Schurman (1636) — an invitation to attend lectures and disputations at the university.[1. Pieta van Beek, The first female university student: Anna Maria van Schurman (1636) (Utrecht: Igitur, 2010), in particular pp. 58– 61.] It is known also that she was tutored in Greek, in Hebrew, and in theology by Gijsbertus Voetius. No other woman was permitted to attend the university in this manner and, thanks to René Descartes, we know Van Schurman had to sit apart in a partitioned cubicle, away from the male students and professors.[2. Charles Adam and Paul Tannery, Oeuvres des Descartes (Paris: Vrin, 1899), pp. 230–1.]

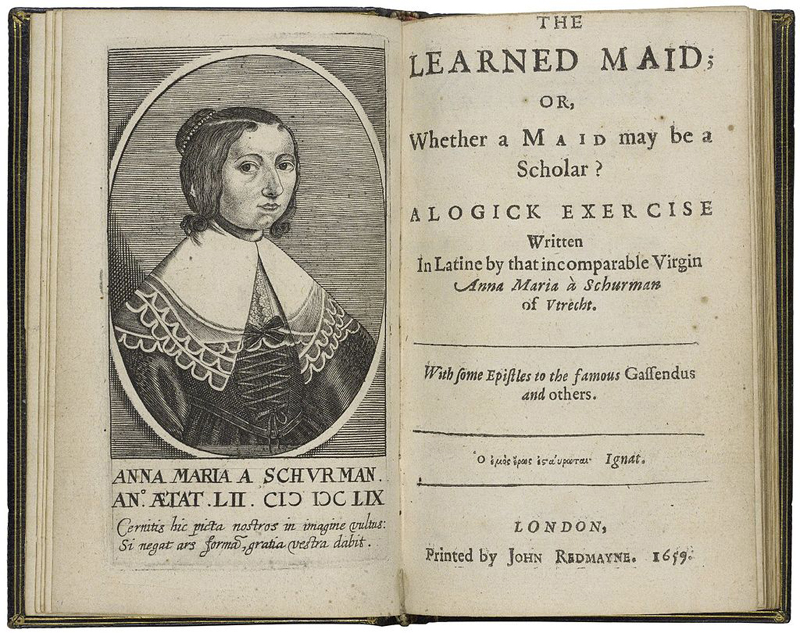

Anna Maria van Schurman, ‘The Learned Maid, or Whether a Maid may be a Scholar. A Logick Exercise’ (London: John Redmayne, 1659.) (Source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

As Van Beek recounts, Van Schurman was referred to by Friedrich Spanheim, the professor of theology at Leiden, as ‘a doctor clothed in women’s robes’.[3. See Anna Maria van Schurman, Opuscula Hebraea Graeca Latina et Gallica. Prosaica et Metrica. Lugdunum Batavorum: ex officina Elseviriorum (Lugdunum Batavorum: ex officina Elseviriorum, 1648), preface.] Her erudition is no less marked in the correspondence she conducted, and Van Beek notes that in Van Schurman’s exchanges with André Rivet we encounter the origins of her published work on the right of women to education, the Amica Dissertatio[4. Amica Dissertatio inter Annam Mariam Schurmanniam et Andr. Rivetum de capacitate ingenii muliebris ad scientias (Paris: s.n., 1638).] and the Dissertatio,[5. Dissertatio De Ingenii Muliebris ad Doctrinam et meliores Litteras aptitudine. Accedunt Quaedam Epistolae eiusdem Argumenti (Lugdunum Batavorum: Elzeviriana, 1641).] which was translated in to French in 1646, and into English in 1659 under the title The Learned Maid, or Whether a Maid may be a Scholar.[6. The Learned Maid, or Whether a Maid may be a Scholar. A Logick Exercise (London: John Redmayne, 1659).] (And what a rallying crying of a title this is!).

Van Schurman’s correspondents were learned and were located across the European continent. Constantijn Huygens wished to marry her; Pierre Gassendi admired her commitment both to scholarship and to celibacy; she resided at the centre of a large network of learned women, including Dorothy Moore, and she corresponded both with Christina of Sweden and the Polish Queen Ludwika Maria [Maria Louise de Gonzaga]. The letters of many of the women in this circle are being worked on at present by members of today’s scholarly network, Women’s Early Modern Letters Online [WEMLO]. Although Van Schurman’s letters may have existed once in their thousands, she seems to have destroyed a large number of manuscripts and papers after she moved from Utrecht in 1669 to join the community that had coalesced around the radical Protestant Jean de Labadie.

Publication in EMLO of this inventory of Anna Maria van Schurman’s surviving correspondence is a first in many respects: the metadata for the letters have been collated by Samantha Sint Nicolaas as part of her internship at the SKILLNET project, where she worked under the supervision of Professor Dirk van Miert with the blessing and support of the Van Schurman scholar, Dr Pieta van Beek. And Van Schurman’s is the first catalogue to be contributed to EMLO by SKILLNET, the first of a large number that will come together as a very significant corpus. SKILLNET has embarked upon a five-year mission to mine the content of early modern epistolaries and investigate how participants in the ‘Respublica Literaria’ transcended political, confessional, and language boundaries to evolve successfully and seamlessly into a pan-European ‘knowledge commons’. Funded by the ERC, SKILLNET has emerged from the cocoon of the European project COST Action Reassembling the Republic of Letters (headed by the Cultures of Knowledge project director, Professor Howard Hotson) and is working closely with EMLO. It is wonderfully fitting that such a remarkable and pioneering female scholar should be the trailblazer for this partnership between SKILLNET and Cultures of Knowledge. Anna Maria van Schurman, Samantha Sint Nicolaas, Pieta van Beek, Dirk van Miert, and the SKILLNET team alike, we salute your invaluable work on the Republic of Letters!

An account by Samantha Sint Nicolaas of the journey she undertook as she visited an array of archives to collate this inventory — ‘Retracing the ‘Grand Tour’ of Anna Maria van Schurman’s Letters‘ — may be found on the SKILLNET blog.