How fitting at the start of a new academic year that the first of a new batch of catalogues to be published in EMLO concerns a society dedicated to the circulation of knowledge. Established by a group of Irish virtuosi, the Dublin Medico-Philosophical Society was founded in 1756 primarily to advance and promote learning and to harness practical knowledge. Its first recorded meeting was held on 8 April that same year and was attended by John Rutty, Charles Smith, Henry Downing, and the Reverend Nathaniel Caldwell. The Society proposed bi-monthly meetings with the intention of discussing papers and news on medical and related matters of interest. Papers read aloud to members at subsequent meetings emulated closely in style those of the London-based Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions and the underlying intention of the Medico-Philosophical Society was to create a forum in Dublin for intellectual and scientific exchange.

Naturally correspondence was central to the activities of the Society and was the primary means by which information from and to national and international contacts regarding medical and scientific practices, advances, and discoveries was conveyed, and the ensuing epistolary discourse ensured participation from Dublin in the far-reaching and wide-ranging debates and discussions of the mid-eighteenth century. It is clear from the surviving correspondence and minute books that the Society was built firmly upon Baconian principles. Charles Smith, in a ‘Preliminary Discourse’, set out that members would conduct ‘medical, natural and philosophical inquiries’ (in line with those that had been established already and were continuing to flourish the length and breadth of Europe). ‘Truth and a sound method of reasoning, first introduced by Lord Bacon’ would enable them to triumph ‘over the errors of former ages and the dark subtleties of the schoolmen’. Worthy ideals indeed for the improvement of medical practice in Ireland.

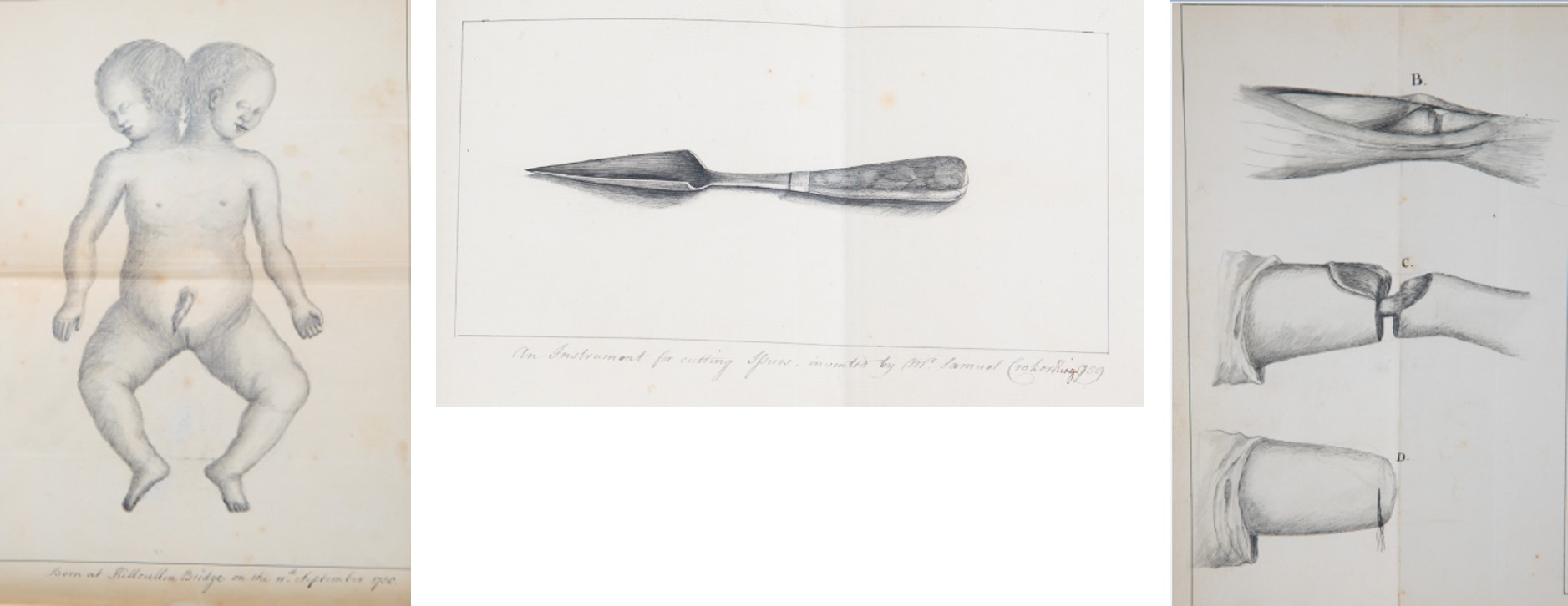

Metadata for the Society’s correspondence has been collected by Oxford doctoral student Rachael Scally, and it is clear from the calendar of letters she has assembled and the research she has conducted around these letters that the Society wished to ‘to furnish [their] quota to the Republic of Letters’.[1. Scally, Rachael, ‘Enlightenment and the Republic of Letters at the Dublin Medico-Philosophical Society, 1756–1784’, University of Dublin, Trinity College, Journal of Postgraduate Research, 14, (2015), pp. 156–78.] Open to all suitably qualified medical professionals, the Society nurtured exchanges with physicians, anatomists, surgeons, male midwives, apothecaries, and natural philosophers. Members were requested to scour newspapers and periodicals for relevant items pertaining to ‘natural history, natural philosophy, medicine, or anything curious or useful in nature or art’ to communicate to their fellow members. They were encouraged also to experiment and to discuss the results. As Rachel details in her article ‘Enlightenment and the Republic of Letters at the Dublin Medico-Philosophical Society, 1756–1784’, John Rutty smelled and tasted his mineral and botanical specimens, in addition to samples of urine (both his own and that of a diabetic patient). Patients in Dublin’s hospitals under the care of the Society’s members participated in medical trials — hemlock, wort, and various unidentified powders sent in by eager correspondents were tested upon them — and underwent carefully documented operations involving different types of surgery. (I advise the squeamish not to follow this blog through to its conclusion as I have placed right at the end what some might find a number of less-than-palatable illustrations which were collected and filed by members of the Society!)

The Society’s members themselves, Scally reveals, had been educated at a number of key European institutions, including those in Leiden, London, Edinburgh, Paris, and Rheims. Rutty had studied under physician and botanist Herman Boerhaave; MacBride had been a pupil of anatomy in London with the Scottish physician William Hunter. Incoming letters read out at meetings were received from as far afield as New York and Montreal and, in addition, many of the members belonged to other illustrious societies (for example, Scally notes that James Span was a European member of the American Philosophical Society).

Sadly, the dream outlined by Smith in his ‘Preliminary Discourse’ never reached fruition. The Society disbanded on 7 October 1784. The reasons for this unexpected and sudden termination are not clear and for theories of shameless academic scheming and skulduggery you should read Scally’s article (details and a link to download the PDF from a subscribing institution may be found by clicking here). Thankfully the machinations involved nothing as toe-curling as the meticulously drafted images I’m attaching below, but the result was a merger of the Society’s members into the Irish Academy, which received a Royal Charter in 1785 and began to publish its own Transactions the following year. What is beyond doubt is that the Dublin Medico-Philosophical Society was instrumental in furthering medical practice in Ireland in the second half of the eighteenth century, and that it paved the way for continued organized discussion from that point forward. We hope you enjoy the Society’s catalogue of correspondence (and for those of a frail disposition this is the final warning to click away … perhaps to Rachael Scally’s blog for the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh about George Cleghorn, the surgeon-anatomist who became a member of the Dublin Medico-Philosophers Society in 1757 having accumulated thirteen-years’ worth of experience on the island of Minorca with the 22nd Regiment of Foot … ).

Three drawings from the ‘Medical and Philosophical Memoirs’. (Images courtesy of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, Dublin)